Our society’s sense of what is fair is constantly evolving.

In the past few years alone, we’ve seen a new candidate and employee expectation around compensation transparency and pay inequity. Many people believe they’re being paid unfairly, and they’re right to feel that way.

Comptech wouldn’t exist as a new industry if there wasn’t a surge in public focus on more equitable practices in the workplace.

While there are numerous reasons why people get paid unfairly (or at least think they are) here’s what our data and experience suggest are the three biggest contributors to this problem.

The Systemic Problem of Unfair Pay

Imagine a recruiter reaches out to you and offers a significantly higher compensation package to quit and come work for their company. It’s a compelling opportunity, so you present this offer to your manager as proof of your market value, hoping to leverage it for a comp increase. Only to have your head of human resources say that they can’t match the offer.

Does this mean your company is cheap and doesn’t care about its people?

Not at all. It may not even be your manager’s fault. The root of the problem is more systemic. There are likely legacy forces at work that are extremely difficult to upend. When your company was founded, the team probably created systems that limit them in what they can and can’t do to compensate fairly.

Oftentimes, the origin of unfair pay goes back to poor compensation practices. Organizations are running merit cycles using outdated, inaccurate compensation data. They’re spending two weeks a year collating hundreds if not thousands of spreadsheets to pull together endless data points, which enable leaders to provide inputs. And this outdated system ultimately leads to error and bias.

Certain employees are paid more than others, regardless of important variables like tenure, geography, experience, performance, and so on.

We empathize with the teams most affected by this systemic problem. Most human resources professionals are so consumed with the operational challenge of compensation, that they simply don’t have the time to achieve fair pay for all. They lack the bandwidth and resources to ensure every person making compensation decisions is making them the same way. And they also lack the macro visibility to spot pay inequities early on.

These poor compensation decisions become exponentially magnified every single merit cycle.

And the next thing you know, the pay delta between a company doing it fairly and company doing it unfairly is too much to fix with a single comp adjustment.

But the system isn’t the only culprit. What about the numbers that run it?

The Data Problem of Unfair Pay

Imagine a colleague asks you the following question: Are you being paid a fair market rate?

Would you answer with a resounding yes, an emphatic no, or somewhere in between?

Most job seekers frankly have no idea. They’re looking for such information as they research opportunities and entertain offers. Leaning on publicly available, experientially based data to anchor their research.

This is certainly better than doing nothing and just ballparking it. But when you study the traditional public records such as Glassdoor or Salary, you’re basically looking back in time. The labor market changes fast, as we saw during the pandemic. Data like that is only calculated once or twice a year, and is outdated as soon as it’s published.

Few candidates (as well as employees) have an accurate grasp about what they are truly able to command in the job market. It’s difficult and time consuming for the average person to gauge salary expectations, equity packages and other aspects of total compensation. Particularly when it comes to startups.

The Pave Data Lab runs the largest real time compensation benchmark data set for venture backed technology companies. If you are currently doing due diligence on your own fair market value, either in your job search or as you grow in your current role, consider these benchmarks:

If you’re a designer with top seniority, your expected salary should be 222k

If you’re a software engineer moving from Boston to NYC, that’s a $24k increase

If you’re applying to jobs with “head of” in the title, it’s actually similar to director level

If you’re applying to a company of 100+, expect around 36% of female employees

If any of the above data points are different compared to what you thought was your going market rate, you’re not alone. Fair pay perceptions don’t always reflect fair pay realities.

Next time you sit down with your boss, hiring manager or a recruiter to talk about salary expectations, you might bring up discussion points like:

- Where are you sourcing your salary data? How recent is it?

- What is this company’s infrastructure of leveling?

- How do my salary bands compare, percentile wise, to similar companies?

If you want to increase your likelihood of fair pay in the future, arm yourself with the above resources to show employers and potential employers that you’re someone who advocates for their marketplace value.

The Communication Problem

Have you ever worked at a company where compensation was not spoken about besides the offer letter? Perhaps once or twice a year during merit cycle season?

Talk about unfair pay. It’s astounding how much asymmetry there is between employees and leadership when it comes to compensation.

In a large percentage of companies, candidates and employees alike are left bewildered about their total comp. They believe their company doesn’t care about helping them understand the more abstract elements like stock options, benefits and so on. And as a result, their impression is that they’re not being paid fairly.

To solve this communication problem, we recommend employers and candidates alike align with organizations that have carefully outlined their compensation philosophy. This is a critical part of ensuring that their company culture is equitable. Everyone should be fortunate enough to work somewhere where the people operations team, executives and managers clarify the “why” behind pay. If your current or prospective employer has a framework to assure consistency across the whole team, that’s a huge step towards getting fair pay.

As we outlined in our ebook, The Guide to Creating Your Compensation Strategy, being hyper intentional about comp philosophy will help companies become thoughtful about compensation decisions, establish a single source of truth for compensation decisions, and last but not least, pay their people fairly.

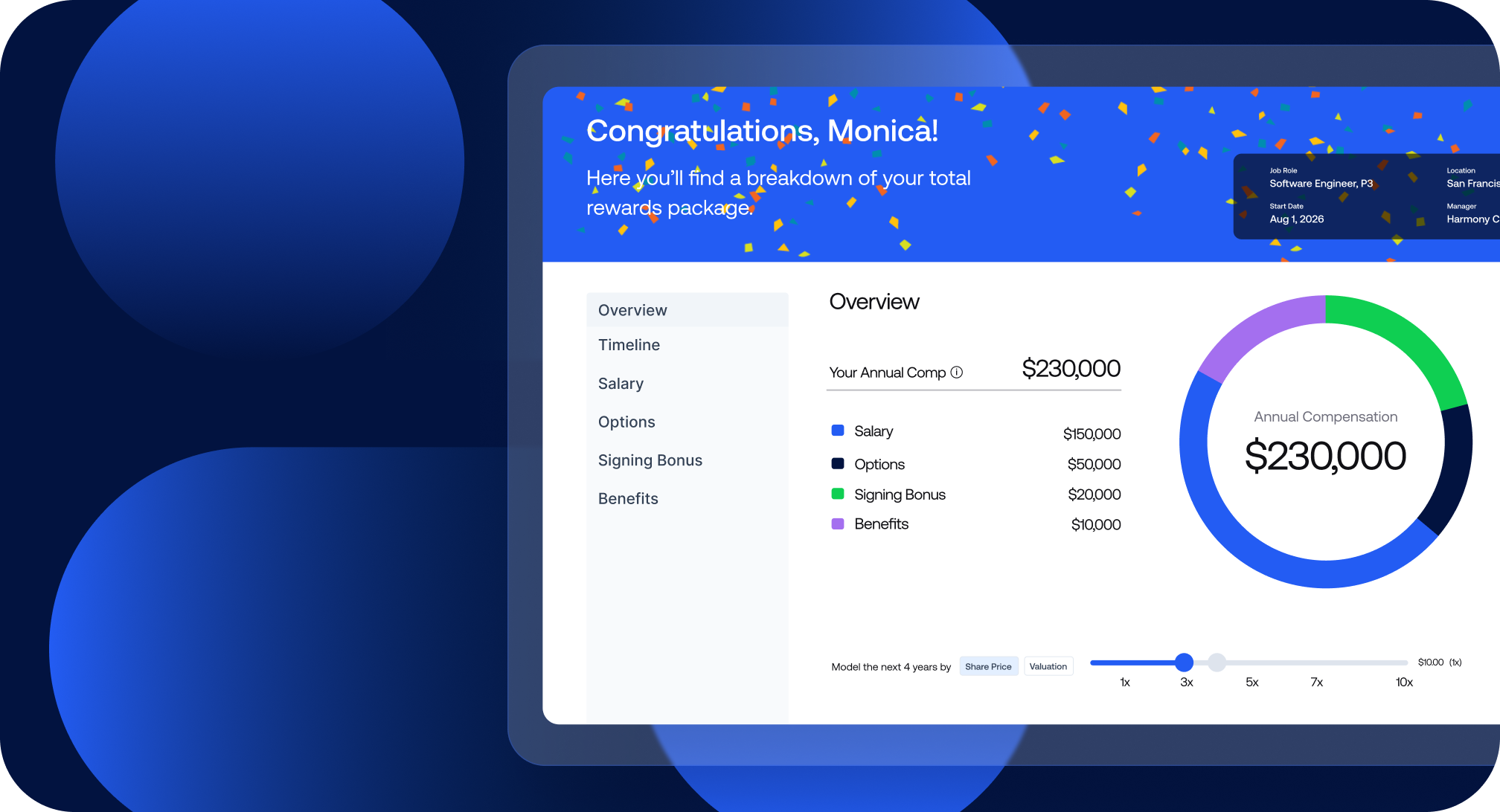

The good news is, the right compensation technology can help companies overcome this last of our three problems. Human resources teams can clearly and compellingly educate candidates and employees using tools like visual offer letters, total rewards portals, historical and future compensation modeling and comp increase messaging.

With a transparent solution like that, it makes it increasingly hard to hide information. Because now everyone is using the same language. Executives, managers, independent contributors and candidates alike are aligned from a communication standpoint. Hype and expectation are kept at bay. And everyone will understand (at any given moment, not just once or twice a year) the business reason for various comp changes and how that impacts them.

Comptech assures there will be no unanswered questions about how pay was determined, and how that may or may not differ from market value.

If you work somewhere that uses technology to help you understand what’s going on behind the curtain and why you should care about it, unfair pay can become a relic of the past.

Ultimately, our society’s collective sense of what is fair will continue to evolve.

People’s expectations around compensation transparency and pay inequity will shift.

If you believe that you’re currently being paid unfairly, consider that the core problem behind that injustice might be a systemic, data or communication issue.

Author of 53 Books. World Record Holder of Wearing Nametags. Busker in Brooklyn. Dogs > Cats.

.jpg)

.jpg)